Cambrian Creatures’ Diverse Complex Eyes Reinforce Creation Narrative

Does evolution or creation better explain the rapid emergence of complex animals? If there’s one event in Earth’s fossil record history that garners more spirited discussion than any other, it would be the Cambrian explosion.

The Cambrian explosion refers to the sudden simultaneous appearance of a broad diversity of the first skeletal animals. These animals manifested, for the first time in Earth’s history, bilateral symmetry, hard body parts, digestive tracts, circulatory systems, and complex internal and external organs. They arrived not just in one or two phyla (basic body plans). Between 50 to 80% of all animal phyla known to exist in Earth’s history appeared within a few million years or less—a geological instant—after the beginning of the Cambrian geological period 543 million years ago. Now, thanks to a new fossil discovery by paleontologists John Paterson, Gregory Edgecombe, and Diego García-Bellido,1 it is evident that the Cambrian explosion is more complex and explosive than previously thought.

One of the phyla that appeared in the Cambrian explosion is Arthropoda, which persists to this day in the form of insects, arachnids (spiders, scorpions, ticks, etc.), myriapods (centipedes and millipedes), and crustaceans. An order within Arthropoda, Radiodonta, existed only during the Cambrian period and included the earliest known large predators. They possessed claws, jaws with rows of teeth, prominent eyes, gills for respiration, and limbs for swimming (see figure 1).

The most famous species member of Radiodonta is Anomalocaris aff. canadensis (the reddish creature in the top right corner of figure 1). Fossils of this creature are

abundant in the Burgess Shale fossil beds in British Columbia, the first discovered evidence of the Cambrian explosion. A few years ago, Reasons to Believe (RTB) took about 40 ministry supporters on an expedition conference to the Burgess Shale fossil beds. Figure 2 shows photos I took of fossils of A. aff. canadensis claws.

Other Burgess Shale–type fossil beds have since been discovered. The most notable one is located in Emu Bay on Kangaroo Island, South Australia (see figure 3).

The Emu Bay Shale has yielded many A. aff. canadensis fossils. These remains reveal well-preserved details of the compound eyes of the species. What Paterson, Edgecombe, and García-Bellido discovered among the Emu Bay shale are new fossils of the compound eyes of another Anomalocaris species, ‘Anomalocaris’ briggsi.

What surprised the three paleontologists was how distinct the compound eyes of each species appeared to be. The two compound eyes of A. aff. canadensis appear on top of two stalks (see figure 1) and each eye measures a little more than 4 centimeters across. Each compound eye consists of 24,000 lenses (see figure 4). The eyes of A. aff. canadensis are optimally designed for hunting prey in well-lit waters.

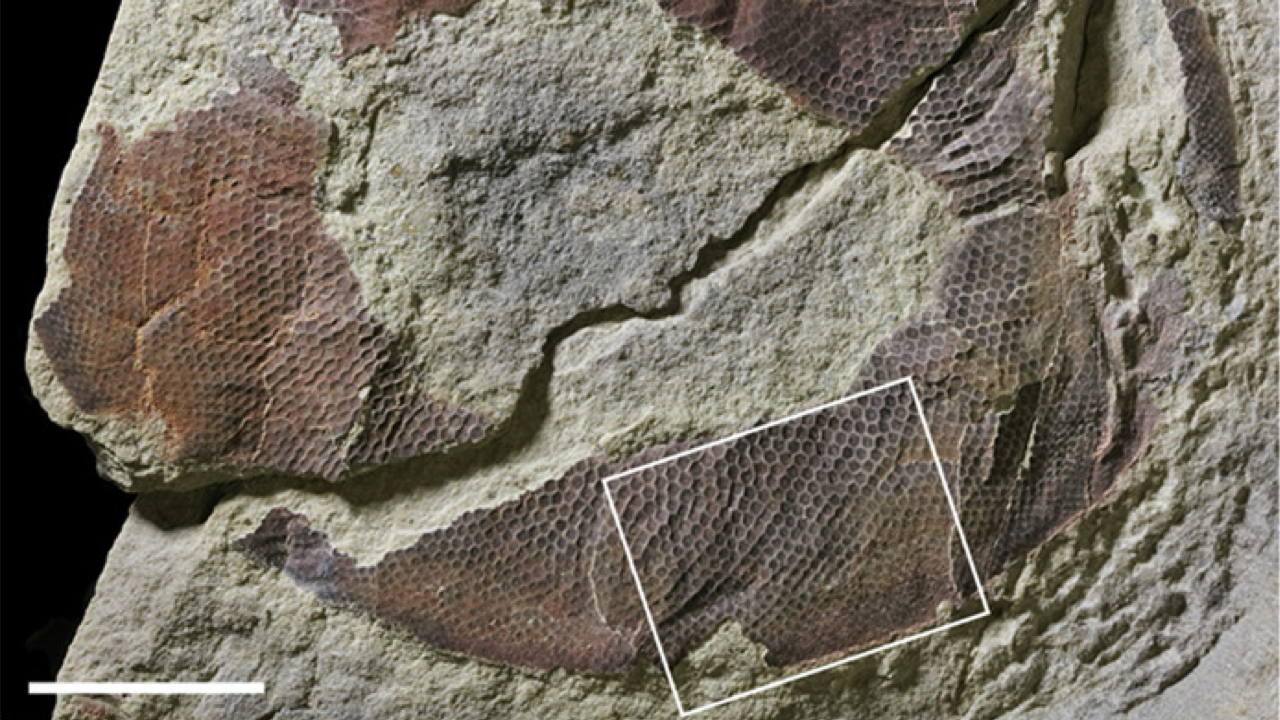

By comparison, the compound eyes of ‘A.’ briggsi are not on stalks. Each eye measures 7–9 millimeters across and consists of 13,000 lenses (see figure 5). The eyes of ‘A.’ briggsi are optimally designed for detecting plankton in dimly lit waters.

Figure 5: Fossil of parts of the compound eye of ‘Anomalocaris’ briggsi. The white bar at lower left = 5 millimeters. Image credit: Paterson, Edgecombe, and García-Bellido, Science Advances 6, id. eabc6721.

Paleontologists have known for several decades that every basic eye design present among animals today was present among the Cambrian explosion animals. This new find establishes that within a basic eye design, Cambrian explosion animals display both diversity and specialization. Paterson, Edgecombe, and García-Bellido’s discovery provides more evidence for biologist Andrew Parker’s 2011 statement on the Cambrian explosion:

At no other time in Earth’s history has there been such a profusion, such an exuberance, and such an overwhelming diversity in so short time, within one million years.2

RTB scholars maintain that such diversity and specialization speak of a Creator’s purposeful design. Moreover, this discovery and the Cambrian event demonstrate more forcibly what evolutionary biologists Kevin Peterson, Michael Dietrich, and Mark McPeek wrote in a review paper on the Cambrian explosion in 2009:

Elucidating the materialistic basis of the Cambrian explosion has become more elusive, not less, the more we know about the event itself.3

Featured Image: Emu Bay Shale Formation

Credit: David Simpson

Check out more from Reasons to Believe @Reasons.org

Endnotes

- John R. Paterson, Gregory D. Edgecombe, and Diego C. García-Bellido, “Disparate Compound Eyes of Cambrian Radiodonts Reveal Their Developmental Growth Mode and Diverse Visual Ecology,” Science Advances 6, no. 49 (December 2, 2020): id. eabc6721, doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc6721.

- Andrew R. Parker, “On the Origin of Optics,” Optics and Laser Technology 43, no. 2 (March 2011): 323, doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2008.12.020.

- Kevin J. Peterson, Michael R. Dietrich, and Mark A. McPeek, “MicroRNAs and Metazoan Macroevolution: Insights into Canalization, Complexity, and the Cambrian Explosion,” BioEssays 31, no. 7 (July 2009): 737, doi:10.1002/bies.200900033.