My Favorite Bible Translations

Almost every time I speak, after the formal Q&A session is over, someone will ask me which Bible translation I use. I frequently shock them when I say I use 40 different translations. Most are stunned to discover that so many different good Bible translations exist. Their next question usually has to do with why I utilize so many translations.

Why So Many English Bible Translations?

There really is a need for 40-plus translations of the Bible. The BibleGateway.com website grants full access at no charge to 55 different English translations of the Bible.1

The primary reason for the need for so many translations is that the Old Testament poses a big problem. The original language is Hebrew except for chapters 2–7 in the book of Daniel. Those six chapters are written in Aramaic.

English is a Roman-Germanic language. Both Hebrew and Aramaic are Semitic languages. Biblical Hebrew, if one omits the names of people and geographical place names, has a vocabulary size of only about 3,000 words. English ranks as the language with the largest vocabulary of all time.2 Large English dictionaries typically include 400,000 words. The second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary defines more than 600,000 words. A search of digitized English language books reveals more than 1 million different words. If one includes names assigned to different species of life and different chemical compounds, the list of English words expands to more than 4 million. Furthermore, the number of new words being added to the English language grows by several thousand per year.

The translation situation is easier for the New Testament, but only somewhat easier. The original language for the New Testament is Koine Greek. The number of Koine Greek words used in the New Testament is less than 6,000.

The size of the English vocabulary accounts for many of the differing translations. Different translations will choose different English words as equivalents for words in the original Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic. The rapid growth of English language vocabulary accounts for many more translations. The growth is such that with the passing of every 15 to 20 years, a new translation is needed to communicate to a new generation of English language readers.

A tension in all English language translations of the Bible is translation philosophy. Translators typically are forced to choose whether to stress literal word-for-word translation from the original Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic or to stress thought-for-thought or meaning-for-meaning translation. Another tension is whether to stress translating the meaning of a text or its intended emotional impact on the reader. Yet another tension is how to translate textual humor, satire, or irony. Still another tension is readability for audiences of different educational levels.

All these tensions explain why there is a need for dozens of different translations. For example, if I want precise descriptions of certain key doctrines like the Trinity, I will consult one of the more literal word-for-word translations like the New American Standard Bible or Young’s Literal Translation. If I want to understand the intended emotional impact of the biblical texts, I will pick up a translation like the Phillips or the Message. If I want to understand the humor, satire, or irony, I will go to the Living Bible or the New Living Bible. If I want a Bible that a young child can enjoy reading, I will give that child a Good News Bible.

My Favorite Bible Translations

In my Bible study and in my research and writing I really do use 40 different translations. However, the translations I use most frequently in my public teaching are what I call compromise Bibles. These are Bible translations that primarily are word-for-word, but where the word-for-word translation yields a clumsy phrase or sentence or where it causes the original meaning or intent of the text to be distorted or misunderstood, a thought-for-thought translation is used.

Good examples of compromise translations are the New International Version (NIV) and the English Standard Version. I have used both, though I prefer the 1984 edition of the NIV to the 2011 edition.

A new Bible translation may become my favorite Bible for public teaching. The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) underwent a major revision and will be re-releasing in March 2017 as simply the Christian Standard Bible (CSB). I got a prerelease copy when I attended an authors’ breakfast at the Evangelical Theological Society conference this past November.

The translation philosophy of the CSB is optimal equivalence. The CSB translation team defines optimal equivalence as:

“Where a word-for-word rendering is understandable, a literal translation is used. When a word-for-word rendering might obscure the meaning for a modern audience a more dynamic translation is used. The CSB places equal value on fidelity to the original and readability for a modern audience, resulting in a translation that achieves both goals.”3

The CSB tackles the gender problem by using generic words or pronouns where the original language clearly implies the inclusion of both sexes. So, for example, the plural of the Greek word, anthropos, often is translated as “people” instead of men as in Romans 5:12. As the translators note in their introduction to the CSB, “While the CSB avoids using ‘he’ or ‘him’ unnecessarily, the translation does not restructure sentences to avoid them when they are in the text.”4

I especially like the footnotes in the CSB. These footnotes will give alternate renderings from competing manuscripts. Where a dynamic translation is used, the CSB often will footnote the literal translation. It also footnotes passages where the Hebrew text is obscure and difficult to translate and in many cases gives the actual Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek words using equivalent English letters.

All these footnotes often spur me to examine alternate translations or to dig out my lexicons and Hebrew and Greek grammar aids. I would say to all students of the Bible that regardless of which Bible translation becomes your favorite, take advantage of the excellent Hebrew and Greek lexicons and Hebrew and Greek grammar aids that exist for English readers. Or, as I say to both Christian and non-Christian skeptics, if you want to nitpick the details of a particular Bible passage, you will need to examine it in the language in which it was originally written. For those of you who like to nitpick the details and for those of you who don’t necessarily feel compelled to nitpick the details, I encourage you both to make 2017 the year when you devote more time to personal Bible reading and study.

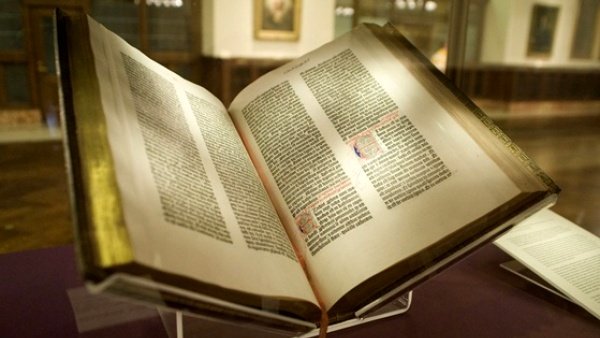

Featured image: Gutenberg Bible, New York Public Library, Lenox Copy. Featured image credit: Kevin Eng

Endnotes

- At this website, BibleGateway.com, one can look up any Bible verse or set of Bible verses in any one or more of 55 different English translations. This website also includes access to Bible translations in dozens of other languages.

- Wil, “How Many Words Are in English Language?” English Live, September 10, 2014, englishlive.ef.com/blog/many-words-english-language/.

- The Holy Bible, Christian Standard Bible, “Introduction to the Christian Standard Bible,” (Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 2017), viii.

- Ibid.

Subjects: Bible, Interpretation, Language

Check out more from Reasons to Believe @Reasons.org